"When childhood dies, its corpses are called adults." - Brian Aldiss

The haunting words of Brian Aldiss—“When childhood dies, its corpses are called adults”—resonate with a chilling truth about the human condition

The haunting words of Brian Aldiss—“When childhood dies, its corpses are called adults”—resonate with a chilling truth about the human condition. As societies worldwide grapple with escalating mental health crises, existential fatigue, and a pervasive sense of disconnection, psychologists, sociologists, and philosophers are increasingly examining the fraught transition from childhood wonder to adult responsibility. This metamorphosis, once celebrated as a rite of passage, is now under scrutiny for what many argue is its role in suffocating creativity, eroding joy, and calcifying the innate curiosity that defines youth.

Childhood, as Aldiss implies, is not merely a phase but a state of being—a realm of boundless imagination, unfiltered emotion, and unstructured play. Neuroscientists point to studies showing that children’s brains are wired for exploration and risk-taking, unburdened by the prefrontal cortex’s later-developed inhibitions. Yet societal systems—education, employment, and cultural norms—often prioritize productivity over play, conformity over curiosity, and pragmatism over passion. “We systematically train children to abandon their innate selves,” says Dr. Elena Marquez, a developmental psychologist at Universidad de Buenos Aires. “By adolescence, they’ve internalized that adulthood means trading imagination for efficiency. The ‘corpse’ Aldiss describes is a life dictated by external expectations, not internal vitality.”

This phenomenon manifests starkly in global workforce trends. A 2023 Gallup poll revealed that 59% of adults worldwide report feeling disengaged at work, citing monotony and lack of creativity as primary factors. Meanwhile, nostalgia industries—from toy brands targeting adults to “kidult” entertainment franchises—are booming, suggesting a collective yearning to reclaim lost fragments of childhood. Yet critics argue such trends commodify rather than cultivate genuine childlike spirit. “Buying a Lego set at 40 isn’t revitalizing your inner child—it’s just consumerism,” argues sociologist Felix Nguyen. “True preservation requires systemic change: workplaces that value play, schools that nurture individuality, and communities that prioritize connection over transactional relationships.”

Cultural attitudes further complicate this journey. In Japan, the term shakaijin (“full-fledged adult”) carries heavy expectations of self-sufficiency and social conformity, often exacerbating isolation among young adults. In contrast, Danish parenting philosophies emphasizing leg (play) as lifelong practice have correlated with higher adult life satisfaction rates. Such disparities highlight how societal frameworks either stifle or sustain the bridges between childhood and adulthood.

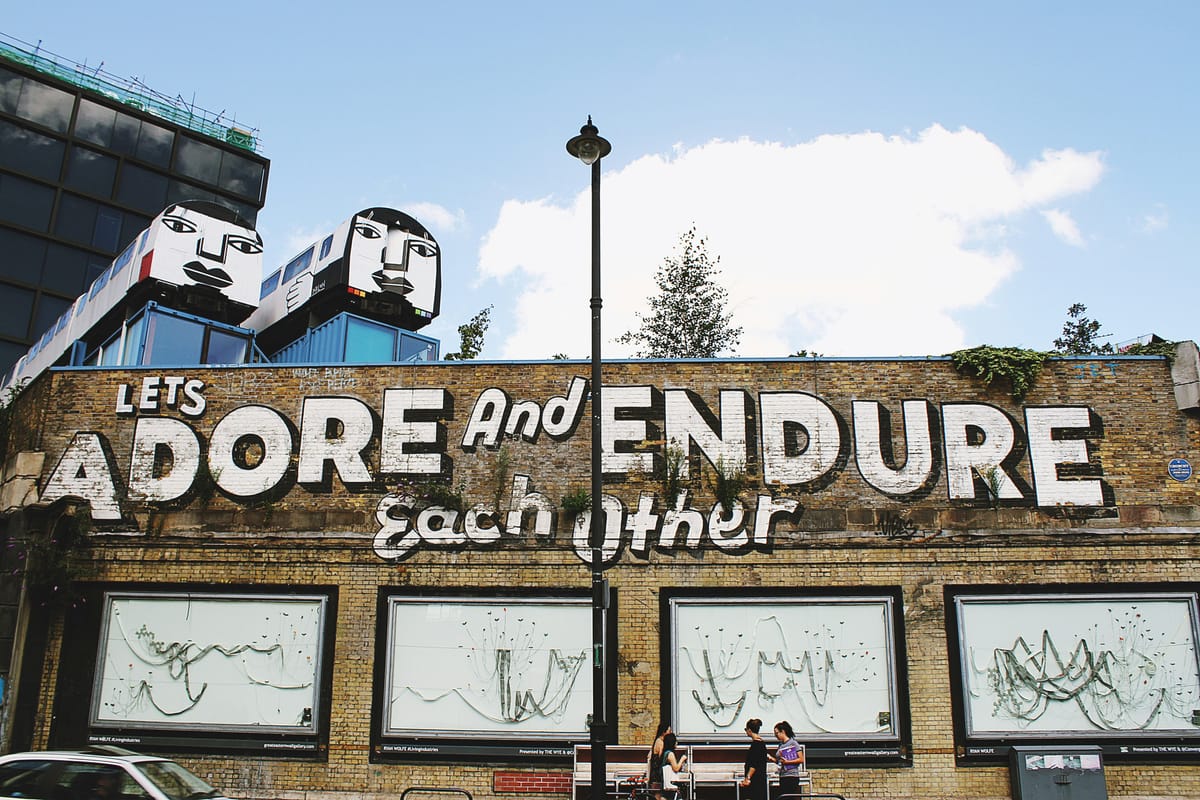

Yet resistance is emerging. Movements like “slow living” and “adult recess” advocate reintegrating spontaneity into daily routines. Therapists increasingly prescribe “play therapy” to adults to combat anxiety, while companies like Google and IDEO mandate “innovation hours” to rekindle creative instincts. Even urban design reflects this shift, with cities like Helsinki and Melbourne investing in public art installations and interactive playgrounds accessible to all ages. “The goal isn’t to reject adulthood but to redefine it,” says author and activist Priya Chaudhry. “Why can’t responsibility coexist with wonder? Why must maturity mean the death of delight?”

Aldiss’s metaphor, bleak as it seems, invites a provocative reframing. If adulthood is the corpse of childhood, perhaps it is also a canvas for resurrection. Psychologist James Hillman’s theory of the “acorn soul”—the idea that each person carries an innate potential waiting to unfold—implies that the traumas of “growing up” need not extinguish the self but could instead inform a more integrated existence. Stories of late-life creativity, from Grandma Moses’ paintings to Julia Child’s culinary triumphs, underscore that the spirit of childhood can resurface when societal shackles loosen.

The challenge, then, lies not in lamenting lost youth but in interrogating the systems that equate adulthood with emotional austerity. As climate crises, political polarization, and technological alienation reshape the world, the need for adaptive, imaginative thinkers has never been greater. Rejecting the notion that growing up requires abandoning play may be less a whimsical ideal than a survival strategy. After all, as Aldiss’s words remind us, corpses do not innovate, dream, or thrive—they merely occupy space. The future may depend on whether adults dare to resurrect what they were told to bury.