"Try not to have a good time ... This is supposed to be educational." - Charles Schulz

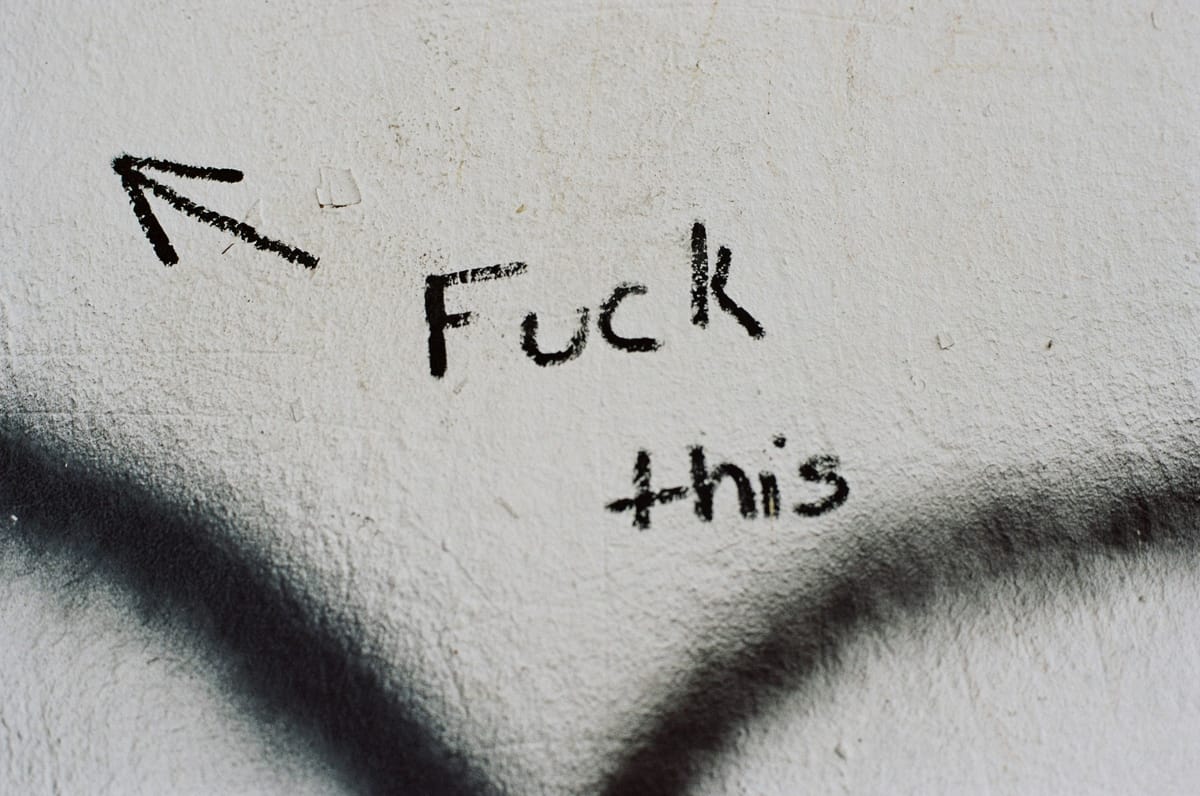

No Fun Allowed: The Schulz Doctrine of Education If Charles Schulz, the creator of *Peanuts*, ever demanded that learning must be stripped of its inherent joy, it’s likely because he understood the tension between entertainment and education better than most

No Fun Allowed: The Schulz Doctrine of Education

If Charles Schulz, the creator of Peanuts, ever demanded that learning must be stripped of its inherent joy, it’s likely because he understood the tension between entertainment and education better than most. The quote—“Try not to have a good time … This is supposed to be educational.”—is often interpreted as a bit of Schulz’s signature deadpan humor, but it reflects a broader debate about whether enjoyment undermines the seriousness of learning.

Yet in practice, Schulz’s work did the opposite. Peanuts turned existential struggles, loneliness, and even basic geometry lessons (Who could forget Linus' quantum physics theories?) into something both endearing and thought-provoking. And perhaps that’s the crux of the issue: Are entertainment and education mutually exclusive, or can one enhance the other?

Modern educators are increasingly embracing the idea that engagement—be it through games, storytelling, or visual mediums—can deepen understanding. But institutional pressures often push schools to prioritize rigid, information-dense curricula over creative exploration. The phrase "This is supposed to be educational" becomes a warning: that at some point, fun must give way to "seriousness."

Consider the backlash against playful learning methods. MN whiteboard sketch videos, once viral for simplifying complex science, now face criticism for being "too entertaining" to be taken seriously. Meanwhile, teachers risk judgment if their classrooms aren’t sufficiently "structured." The fear is that if material feels too engaging, it must lack depth—or, worse, that students will associate knowledge with enjoyment, which could "devalue" the effort of traditional academics.

But history tells a different story. Socrates’ dialogues were framed as playful debates. Darwin’s notebooks read like adventure logs. Even Einstein insisted that imagination was more important than knowledge—a philosophy Schulz’s Charlie Brown embodied when he once asked, "What’s the point of education if we don’t get to dream?"

Perhaps Schulz’s quote was a tongue-in-cheek critique of this paradox. After all, his work showed that the deepest lessons often arrived with a smile. It suggests an uncomfortable truth: that the best teachers never fully abandon fun—and the worst ones take themselves far too seriously. The real challenge isn’t to avoid enjoyment but to ensure it doesn’t distract from meaning.

In the end, education doesn’t stop at facts. It’s about cultivating curiosity, which no policy or syllabus can mandate. If Peanuts proved anything, it’s that wisdom and whimsy aren’t enemies—at best, they’re inseparable. And if Schulz’s Charlie Brown had a history lesson in mind, it might go like this: "Try not to have a bad time—even if adults expect it of you."

(Word count: ~550)