"Authors are easy to get on with" - if you're fond of children. -- Michael Joseph, "Observer"

Opening Hook: "Authors are easy to get on with," remarked the late publisher Michael Joseph in the Observer decades ago, "if you're fond of children

Opening Hook:

"Authors are easy to get on with," remarked the late publisher Michael Joseph in the Observer decades ago, "if you're fond of children." At first glance, it seemed a throwaway, witty line. But spend any time observing the writing life, talking to agents, editors, partners, or the authors themselves, and Joseph's observation reveals a profound, often unspoken truth about the creative temperament. The chaotic energy, the intense emotional swings, the peculiar demands for specific biscuits... sound familiar? For those accustomed to the world of young children, navigating the landscape inhabited by many professional wordsmiths feels strikingly similar, underscoring a deep connection between uninhibited creativity and the unselfconscious nature of childhood.

The Core Similarity: Imagination Unleashed:

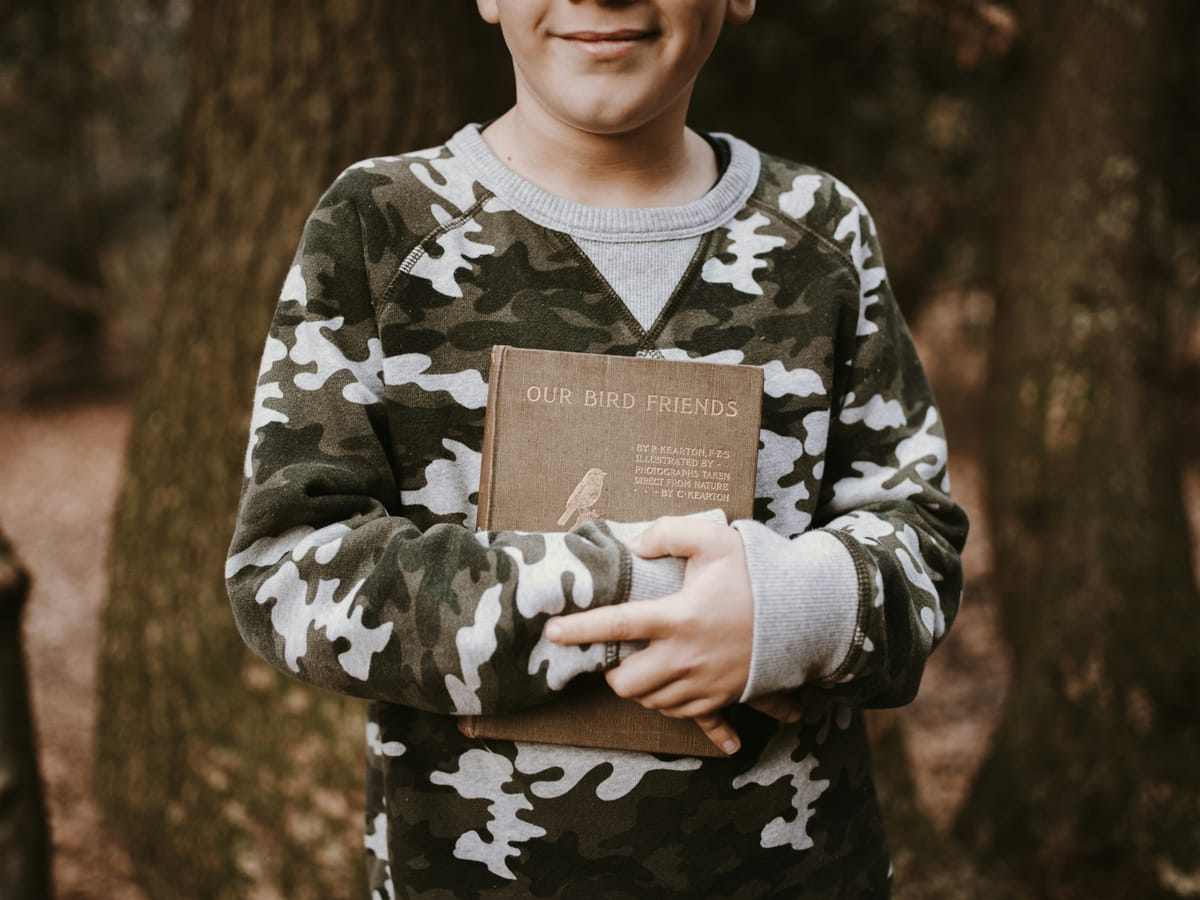

Ask anyone who regularly cares for small children: their worlds are governed by internal landscapes teeming with dragons, invisible friends, complex social scenarios acted out with stuffed animals, and the conviction that a blanket fort is a castle. Authors, locked in the throes of creation, inhabit a near-identical headspace. They converse with characters only they can see, become obsessed with the minutiae of fictional worlds (why does the protagonist always drink Earl Grey?), and mentally rearrange reality on a whim. An editor scheduling a call might as well be interrupting a five-year-old mid-space battle – the transition back to mundane reality can be jarring, often accompanied by visible frustration or distracted vagueness.

Quirks and Rituals: From Bedtime Stories to Writing Caves:

Just as a child might demand the exact blue cup or insist on bedtime stories told in a specific cadence, authors develop intricate, often non-negotiable rituals. The right pen. The specific, often chaotic, writing den (Virginia Woolf’s Room of One’s Own frequently resembles a toddler’s playroom in its state of creative disarray). Silence must be absolute, or perhaps specific ambient noise is essential. A particular brand of coffee, a specific time of day, a lucky charm. These aren't mere preferences; they are the scaffolding that holds the fragile, immersive state of creation together, as vital to the writer as a well-worn security blanket is to a small child weathering a storm.

Emotional Volatility and Need for Nurture:

The emotional parallels are perhaps the most potent. Authors, like children, experience joy and despair with startling intensity. A brilliant paragraph can induce giddy euphoria. A harsh review, a plot hole that won't resolve, or a rejection letter can plummet them into a black mood resembling nothing so much as a toddler denied ice cream before dinner. Patience is required. Understanding that the sulk (or the writer's block) will pass is essential. So too is the understanding that they need feeding – literally, but also metaphorically: encouragement, reassurance, and sometimes just space until the storm within passes. They crave praise for their "shiny thing" – the new chapter, the clever turn of phrase – mirroring a child proudly presenting a messy finger painting.

Seeing the Magic Through Their Eyes:

Furthermore, those "fond of children" understand the ability to see the world differently is a gift, not an annoyance. The parent marvels at their child seeing a knight in a cardboard box; the supportive partner or editor marvels at the author spinning a novel from a snippet of overheard conversation. This appreciation for unconventional perspectives, for leaps of impossible logic that somehow work, fosters the empathy needed to navigate the author's world. They recognize the raw vulnerability beneath the ego, the fierce protectiveness an author feels for their manuscript echoing a parent's fierce love.

Real World Examples and Nuances:

Think of J.K. Rowling feverishly writing early Harry Potter drafts in an Edinburgh café, her pram beside her – simultaneously embodying both author and parent. Recall George Orwell writing in bed with tea constantly brewing, or the famously idiosyncratic routines of writers like Victor Hugo demanding nudity before dawn to write. The anecdotes paint a picture not of eccentricity for its own sake, but of minds accessing a state where conventional adult rules of behaviour are temporarily suspended in service of creation.

Of course, this isn't universal – weathered war correspondents or meticulous journalists might project a different veneer. But for the archetypal novelist, the short story writer dwelling deep in internal realms, Joseph’s observation resonates. Engaging with them successfully requires the same reserves of patience, flexibility, good humour, and unconditional (though sometimes exasperated) appreciation that caring for a highly imaginative child demands. It requires accepting the inevitable messiness of the process, celebrating the moments of pure wonder they conjure, and understanding that sometimes, the best thing to say is simply, "Show me your story." The reward, much like seeing a child absorbed in joyful play, is witnessing pure, unadulterated imagination take flight, even if it means tripping over a pile of reference books in the hallway.