"As far as we know, our computer has never had an undetected error." - Weisert

In a statement that has sent ripples through the technology and academic communities, Dr

In a statement that has sent ripples through the technology and academic communities, Dr. Carl Weisert, a noted computer scientist, recently declared, “As far as we know, our computer has never had an undetected error.” The remark, made during a symposium on computational integrity at the University of Chicago, was not delivered as a boast but as a sobering provocation, challenging the very foundation of modern software development and system design.

Weisert’s assertion centers on a meticulously maintained legacy system, a machine running critical administrative and research functions for a private institute. Unlike modern distributed systems comprising millions of lines of code and countless interdependent modules, this computer operates on a relatively simple, closed, and exhaustively documented stack. Its tasks are well-defined, its hardware is stable and unchanging, and its operational history is logged with fastidious detail. For over two decades, a small team of specialists, including Weisert himself, has curated its environment, rejecting unnecessary updates and rigorously testing every single alteration before implementation.

“The key,” Weisert elaborated in a follow-up interview, “is not a claim of infallibility, but a methodology of extreme transparency and limitation. We do not say errors are impossible. We say that our process is designed to make any error, should it occur, immediately apparent. We have never encountered a discrepancy between expected and actual output that we could not trace back to a documented change or a diagnosed hardware fault. Therefore, to our knowledge, no error has ever gone undetected.”

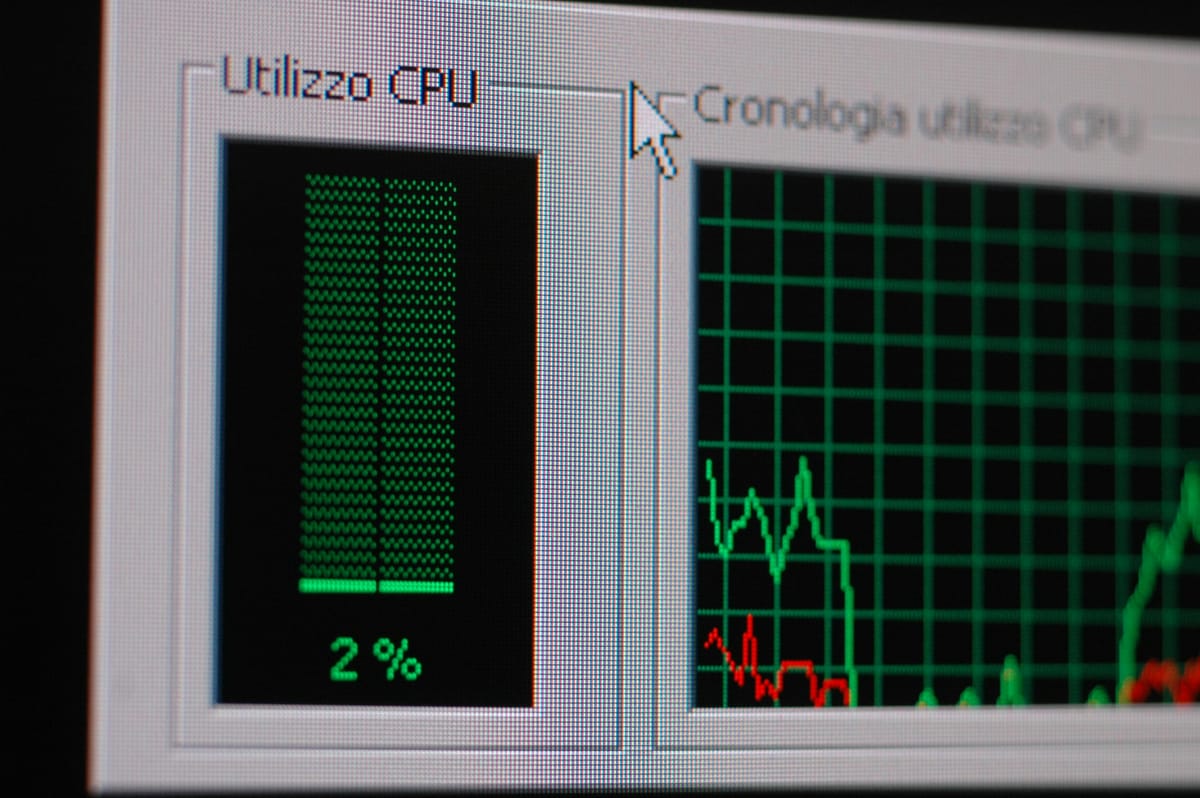

The reaction from the broader tech industry has been one of fascinated skepticism. Janet Morales, a lead engineer at a major cloud services provider, called the claim “a beautiful anachronism.” “In our world,” she said, “the scale is so vast that we operate on the assumption that undetected errors are not just possible, but are a constant. Our entire DevOps culture, our monitoring suites, our canary deployments—they’re all built around detecting and mitigating errors we know must be happening. Weisert’s model is like a master watchmaker claiming his single, hand-crafted timepiece has never been wrong, while we’re managing a global network of millions of digital clocks, all ticking at slightly different rates. Both can be true, but they exist in different universes.”

Ethicists have also weighed in, pointing to the profound implications of Weisert’s statement. Dr. Alisha Fenway from the Center for Technology Ethics noted, “This isn’t just a technical issue; it’s a philosophical one. It forces us to ask: what does it mean for a system to be ‘correct’? Is it the absence of known errors, or is it a provable state of perfection? In most practical applications, we have to settle for the former. Weisert’s team seems to have created an environment where the two states are nearly congruent, but that requires a level of control and isolation that is simply impossible for the systems governing our power grids, financial markets, or social media platforms.”

The debate underscores a growing tension in an increasingly automated world. As society cedes more authority to complex algorithms and black-box AI systems, the inability to guarantee their flawless operation becomes a critical vulnerability. Weisert’s closed system, while seemingly a relic of a bygone era, presents a compelling, if unattainable, ideal: a complete and perfect understanding of one’s tools. His statement serves less as a benchmark for others to meet and more as a poignant reminder of the inherent trade-offs between scale, complexity, and the elusive goal of true computational certainty. In the end, the most significant undetected error may be the unquestioning faith we place in systems whose inner workings we can no longer fully comprehend.